Understanding British Portraits and The Health of the Munition Worker

As Curator at The Devil’s Porridge Museum, my research primarily focuses on social history and how people lived and worked during the First World War. I’ve followed the UBP network for some time, and particularly enjoyed 2022’s Annual Seminar which helped me to reflect on some of my own work.

But first, a bit of context is needed! The Devil’s Porridge Museum isn’t actually about porridge, or the devil for that matter. It tells the story of HM Factory Gretna, the largest munitions factory in the world during WWI. It was 9 miles long and 2 miles wide and at its height employed 30,000 workers. The townships of Gretna and Eastriggs were created to house them, transforming a quiet rural area into a bustling industrial hub. The legacy of this was largely forgotten until 1997 when a group of volunteers set up an exhibition in St John’s Church in Eastriggs. 25 years later, The Devil’s Porridge is an accredited museum in a purpose-built facility, and a Visit Scotland 5-star rated attraction.

But why is it called The Devil’s Porridge? Arthur Conan Doyle, of Sherlock fame, visited the factory in 1916 as a war correspondent. Observing the girls mixing cordite in massive pots, he claimed it looked like they were ‘making the devil’s porridge’.

Whilst WW1 has been extensively researched, we feel that the lives and hardships of munitions workers on the Home Front is often overlooked - both in popular history and in academia. One reason for this is the lack of records. Our Miracle Workers project seeks to go some way to alleviating that. This database is, we believe, the very first of WW1 munitions workers to be available publicly, and serves both as a lasting legacy for the project and as a knowledge base for those researching WW1 munition workers. [ https://www.devilsporridge.org.uk/hm-factory-gretna-miracle-workers-database]

Early research soon identified that a high number of workers at HM Factory Gretna were disabled, and until now their stories have remained untold. This spawned our 2022 exhibition and publication The Health of the Munition Worker: A Disability History of the World Wars on the Solway Military Coast.

Some workers arrived in this area already disabled and declared unfit for war service, so sought to ‘do their bit’ for King and Country through munitions work. Others were left with lifelong disabilities and chronic illnesses because of their wartime work - limb loss, breathing difficulties and burns were amongst the common conditions. All, however, risked life and limb to aid the war effort in both global conflicts of the twentieth century. Their contribution has not been adequately recognised by historians and museums—this exhibition hopes to go some way towards changing this.

But how does this relate to the UBP 2022 Annual Seminar?

As part of our Disability: Past and Present project, this exhibition sits alongside an accessibility audit, a series of talks with disability historians, outreach work with local disability groups, a published book containing our historical research, and a cartoon created by disabled filmmakers FilmAble. It struck me how similar this approach is to The Colonial Legacies of the Liverpool Sandbach Family: A community-led research and display development project at the Walker Art Gallery, presented by Alex Patterson, Assistant Curator of Fine Art. Increasingly, it has been shown that when researching and interpreting hidden or contested histories it is vital to include community-led research with the relevant affected minorities.

I was also found myself reflecting on the portraits unearthed through our disability research in relation to Dawn Kanter’s paper on Understanding British portraiture 1900-1960 as a network of linked portrait-sitting exchanges. Most portraits, whether paintings or photographs, of munitions workers show them diligently at work or in a heroic pose in support of the war effort. They don’t showcase the realities and dangers of the work, or how it drastically changed people’s lives. In fact, there was very often no relationship between the artist and the sitter; most images were recorded for propaganda purposes or as record photography. The two case studies I want to highlight here are slightly different – they are personal photographs of the sitters as opposed to portrayals of them at work, and what’s striking about them is what they don’t show.

Photograph of William Haddon during his time at HM Factory Gretna; DPM.2022.4193. © The Devil’s Porridge Museum

William Haddon came to work at HM Factory Gretna during WW1, having been declared unfit to serve in the armed forces because he was disabled. William had kyphosis, or curvature of the spine, which can result in chronic back pain and respiratory system problems, and William had to get all his clothes custom made so that they fit him properly. In his own time William was known as a ‘humpback’.

This portrait of William dates from his time at the factory, when studio photography was a common activity for ordinary people, yet you can see no evidence of his disability. Was this William’s choice due to attitudes to disability at the time?

William was first appointed as an ‘Assistant to Assistant Paymaster’ at Gretna, but soon rose through the ranks to become Paymaster in January 1919, on a salary of £300 per year. However, in 1921 he lost his job due to a government policy of employing ex-servicemen wherever possible. The irony of this policy decision is clear: William, a disabled civilian, was being let go by his employer so that they could instead employ a veteran. William protested his dismissal, to no avail.

Jessie Moffat was born in 1922, and began working in munitions at ICI Powfoot, which lies 6 miles to the west of Gretna, the same year it opened in 1941. This studio photograph of Jessie was taken in 1942.

Photograph of Jessie Moffat, age 19, taken before the accident; DPM.2022.4185.1. © The Devil’s Porridge Museum

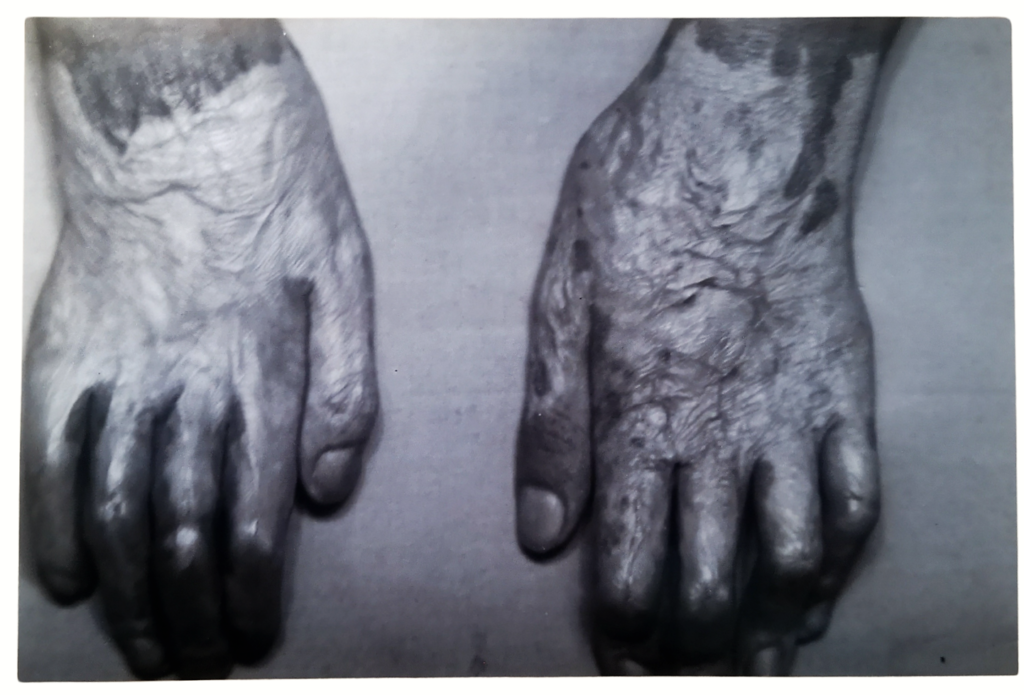

On 17th October 1943, there was a fire and explosion at ICI Powfoot that killed five women. Jessie was severely injured in this accident, suffering injuries that resulted in a life-long chronic condition. She needed multiple skin grafts on her face, and had no eyelashes or eyebrows. Her hands were treated with paraffin baths and fixed in a singular position. She had to sleep with her eyes open as she couldn’t close them, which I find very difficult to imagine. While her great-niece has generously donated photographs of Jessie after her accident, it is her wish that we do not share those of Jessie’s face.

Doll made by Jessie Moffat while recovering from her injuries in Edinburgh Hospital, 1943; DPM.2022.4184. © The Devil’s Porridge Museum

During her treatment at Edinburgh Hospital, Jessie handmade this incredible doll. We’re not sure whether this was done to make sure the dexterity in her hands and fingers didn’t deteriorate after acquiring her injuries, or if she made it as self-portrait, post-accident. If you look closely at the doll, you will see that there are marks and indentations on its face.

I hope I’ve managed to highlight the difficulties of portraiture in relation to munitions workers and shed some light on these untold stories for you. I’ve of course only scratched the surface in this short blog post, but you can purchase a copy of our book to read more about definitions of disability and discover more detailed case studies: https://www.devilsporridge.org.uk/product/the-health-of-the-munition-worker

You can find out more about the Disability: Past and Present project here: https://www.devilsporridge.org.uk/collections/disability-past-and-present-research-project

Watch all of the presentations from the conference here.